Ladino; the five-hundred-year-old language of Istanbul

One of the oldest languages of Istanbul, Ladino has a 550-year history in Istanbul. Ladino is the common name used for Judaeo-Spanish.

Language, like all other cultural assets, is a living organism and evolves over time. Like other languages, Ladino too went through many changes. Even before the Spanish Jewry had abandoned their homeland, the foundations of the modern Spanish were not yet laid. The political unity of the Spaniards in 1492 was the first step on this path. Ladino’s backbone was predominantly a sub-branch of the Castilian Spanish.

Spanish King Ferdinand

The story of Judeo-Spanish or Ladino in the Ottoman lands more or less started in 1492. King Ferdinand and his wife Isabella finally defeated Emirate of Granada thus removed the last obstacle in front of transforming Spain into a Catholic state.

King Ferdinand issued the Alhambra Decree less than three months after the surrender of Granada. Spain’s entire Jewish population was given only four months to either convert to Christianity or leave the country.

Alhambra in Spain was the home to Muslims and Jews in middle-ages

In response to the Alhambra Decree, sent the Ottoman navy under the command of Kemal Reis to Spain to save Jews who were expelled.

Thesaloniki was one of the main hubs for the Ottoman Jews

As a result, many Jews living in Spain had to leave for nearby countries like England, Holland and Italy. Many Spanish Jews also fled to the Ottoman Empire, where they were given refuge. Sultan Bayezid II of the Ottoman Empire, in response to the Alhambra Decree, sent the Ottoman navy under the command of Kemal Reis to Spain to save Jews who were expelled. The Jews settled in Ottoman lands, mainly to the cities of Thessaloniki (currently in Greece) and Izmir (currently in Turkey).

Interestingly, while the Jews outside the Ottoman state ended up adopting the language of their new homelands in a short period of time, the Ottoman Jews kept their loyalty to their language Ladino, up to this day, albeit with some exchange. This is explained by Avram Galanti in his work “The affect of Turkish language on Spanish”: When Jews emigrated from Spain to Ottoman Empire, there was no printing house however Jews brought with them the printing presses to print in their own language. Thus they were able to publish with the Rashi script.

Ottoman Jewish couple in Thessaloniki

Jews migrating to other European countries, ended up adopting the language of that country as there were already local printing houses operating in those countries.

Galata region – Istanbul

Another important factor was the “Millet system” of the Ottoman Empire. Within the framework of millet system, different ethnic or religious groups in the Ottoman Empire were allowed to organize their own tradition, legal systems, education and cultural activities themselves, thus preserving their originality.

Ladino’s impact

Before the Sephardi emigration, languages such as Greek, Arabic and Yiddish were spoken among the Jews living under Ottoman rule. For examples, the Romaniots, who formed the most crowded Jewish community in the Ottoman territory, were speaking Greek. However after Sephardic immigration Ladino became the most effective language among Jewish society over time.

By the seventeenth century, the Byzantine Jews who originally spoke the Greek language, started using Ladino gradually.

Ladino took a significant portion of the religious terms from the Spanish but did not neglect Jewish faith in doing so. One of the most interesting examples in this sense is the removal of the “s” from the Spanish word “Dios” (which means ‘God’), which added plurality.

Jewish officers in Ottoman army

Interaction between Turkish and Ladino

From the seventeenth century onwards, the Turkish words in the Judeo-Spanish language increased drastically.

The interaction between languages started with tax names and other words in the commercial space such as food and beverage names, various animal names, clothes, furniture, everyday goods and professional terms.

Naturally some words from Turkish also passed onto Ladino, such as çarık /çarukas (sandal) or fistan /fostan (dress). On the other hand, some of the words used in Ladino also naturally go to Turkic, among them the most known of which are kashar (from kasher), sponge, bastard and bullshit.

Jewish folk culture was another channel of interaction with Turkish language. As the Jews had a rich culture of folk art, artistic fields such as puppetry, dance, instrumentalism, theater and folk dancing were easier to interact with. Turkish Nasrettin Hodja jokes passed on to Jewish culture as ‘Coha stories’.

El Tiempo newspaper

Ladino during the later stages of the Empire

Ladino language suffered serious tremors from two important developments; the first one was the opening of Alliance Israélite Universelle schools.

The French language became popular among the students who graduated from these schools. However, this also was a positive for the Ottoman-Jewish society. The Jewish community had become a closed society and had lost its prestigious position in the Ottoman Empire to Armenian and Greeks from 17th century onwards.

After the French revolution, the nationalist movements among the Greek and Armenian communities accelerated separatism in these communities however it helped the Ottoman Jewish community come to spotlight again. French speaking members of the Ottoman Jewish society who completed their education in Europe started obtaining respectable positions in the Ottoman State replacing Greek and Armenians. Ladino received a lot of words from the French during this period.

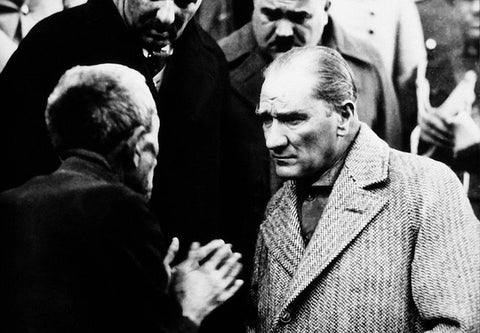

Moiz Kohen was a supporter of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s unification policy

Ladino during the early republican era

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the newly-found Turkish state wanted to unite its subjects via Turkish language. With the union of education (“tevhid-i tedrisat”) law, the new government ensured all schools adopting the same curriculum and language.

Turkish government’s “Citizen, Speak Turkish!” campaign was also a contributing factor.

Moiz Kohen, who was an important figure in the history of Turkish Nationalism, and Avram Galanti, suggested that the Turkish Jews should be Turkified as soon as possible. They suggested that Jewish children should be sent to Turkish schools, and Jewish community should speak Turkish at home and that Turkish names should be given to children.

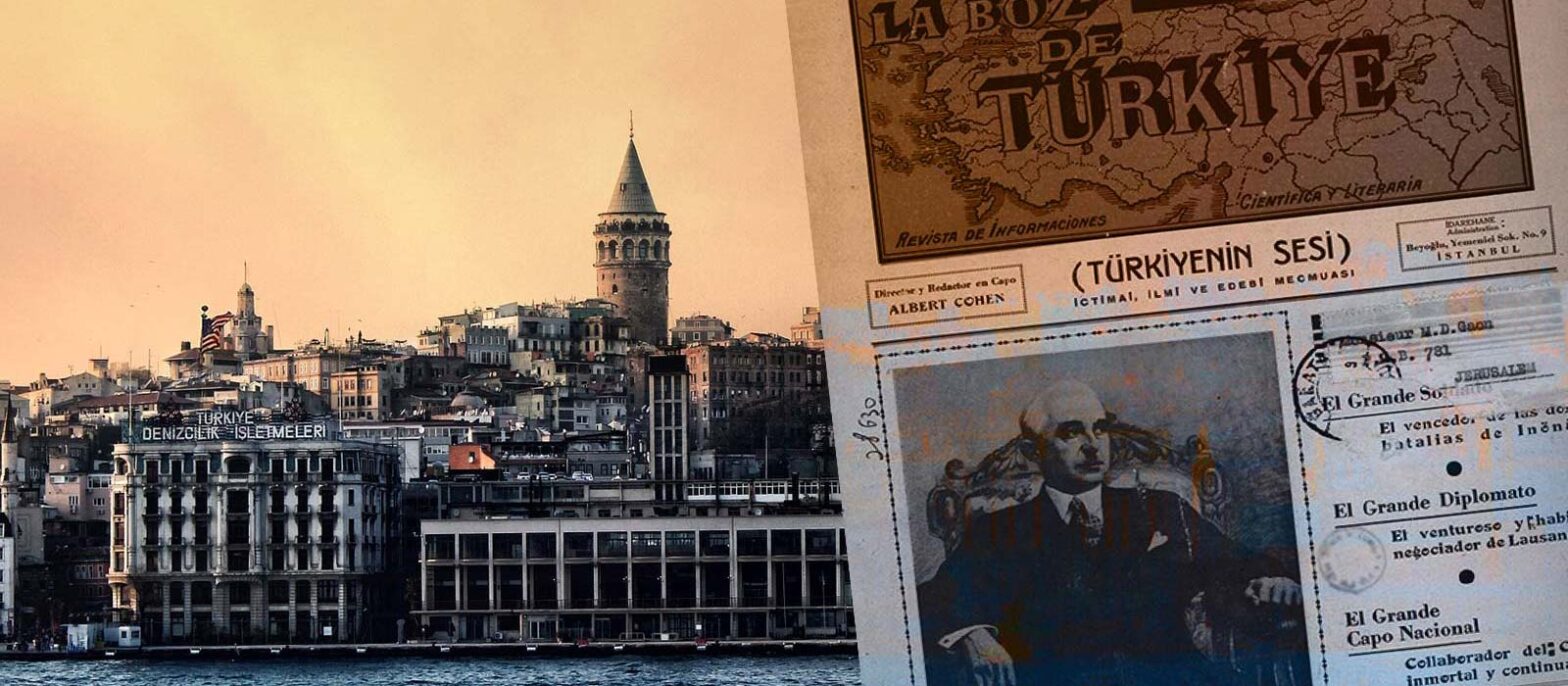

The changes in the language and the culture were also reflected in the field of printing. In the first years of the Turkish Republic, El Telegrafo and El Tyempo were published in Judeo-Spanish using Hebrew letters, while La Boz de Oriente was published half in Latin letters and half in Hebrew letters. A latter newspaper La Boz de Turkiye was not printed in Hebrew letters but rather printed half in Turkish and half in Judeo-Spanish with some French content.

“Citizen, speak Turkish” campaign on Cumhuriyet newspaper of Gönen dictrict of Balıkesir on May 21st of 1936

Once widely spoken by the Jewish communities throughout the Balkans, Turkey, the Middle East and North Africa, Ladino is in a serious danger of extinction because many native speakers have not transmitted the language to their grandchildren.

Shalom, the only newspaper of the Jewish community in Turkey, dedicates a separate page to Ladino language as well offering a monthly extra “El Amaneser” in Judeo-Spanish.

This article was largely based on Önder Kaya’s article on Shalom